Judy Malloy’s Seat at the (Database) Table

a Feminist Reception History

Before I read Jill Walker Rettberg’s excellent “Electronic Literature Seen From a Distance: The Beginnings of a Field,” I’d suspected that Judy Malloy’s elision from the electronic literature reception history as the first author of hypertext fiction was attributable to genre. Her comic piece Uncle Roger, a romp through Silicon Valley set in then-present day 1986, didn’t evince the seriousness, ambiguity, and intricate plotting that critics and other purveyors of taste associate with high art. I accepted without question Robert Coover’s 1992 declaration of Michael Joyce‘s afternoon, a story as the “granddaddy of full-length hypertext fictions,” even though Judy’s Uncle Roger pre-dates Michael’s afternoon by at least one year and possibly three, if one measures from afternoon‘s publication date (1990) rather than its introduction to the coterie of enthusiasts who exchanged stories authored on Hypercard and other systems.

Afternoon is a magnificent work that merits its august reputation.

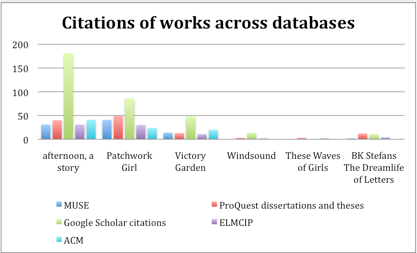

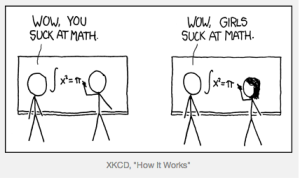

But Rettberg traces the far-reaching implications of Joyce’s reputation in her distant reading, which demonstrates that afternoon is–by an order of magnitude–the most cited and taught work of electronic literature. The status Coover conferred on afternoon in his New York Times review became a self-fulfilling prophecy. It’s such a small thing, just one sentence in the Times; but its impact has been field-defining. Several factors converged to anoint Michael Joyce and submerge Judy Malloy. This talk sketches them with the purpose of seeing how machinic & human procedures collaborate to create conditions that make it less likely women authors will thrive.

Individual actors like Michael Joyce, Judy Malloy and Stuart Moulthrop — all of them pioneers of hypertext in the late 1980s and early 1990s — evinced companionable interest in each other’s work. But the database systems by which that work was shared, discussed & preserved, or NOT shared, discussed and preserved bear the traces of human cultural values & biases. Michael Joyce’s fame and Judy Malloy’s relative obscurity are products of dialectics of inclusion & exclusion that replicate, with numbing fidelity, the traditional privileges that digital media have the capacity to disrupt but often do not.

John Scalzi redescribes white male privilege as a role playing game. He writes:

How to get across the ideas bound up in the word “privilege,” in a way that your average straight white man will get without freaking out about it? Being a white guy who likes women, here’s how I would do it:

Okay: In the role playing game known as The Real World, “Straight White Male” is the lowest difficulty setting there is.

This means that the default behaviors for almost all the non-player characters in the game are easier on you than they would be otherwise. The default barriers for completions of quests are lower. Your leveling-up thresholds come more quickly. You automatically gain entry to some parts of the map that others have to work for. The game is easier to play, automatically, and when you need help, by default it’s easier to get.

Scalzi’s is a great description of how sexism can happen without malice or even intention. In an interview with Jill Rettberg, Stuart Moulthrop describes how at the 1989 Hypertext conference he, John McDaid, Michael Joyce and Jay Bolter sat at a computer connected to the Internet and searched for other people doing similar things. They found Judy Malloy’s work:

“It was just like blues men going to each other’s performances. Yeah, allright, oh darn that’s good. Oh, we’re not that good. So we really recognized that she was somebody, and she was part of a community out there in the Bay Area that was really important and exciting. I can remember coming away from that moment thinking that, you know, there might be a real hope for what we were trying to do because other people were doing it. (Moulthrop, personal interview, cited in Rettberg, “Distant Reading”)

Michael Joyce, Stuart Moulthrop and many of the men I know in the e-lit community are feminist supporters who individually act to redress power imbalances when brought to their attention. Michael and Stuart are tenured full professors at elite universities. None of the pioneering e-lit women authors I’ve met occupy the tenured positions that their male colleagues earned. Just one decade later, in the early 2000s, women e-lit artists did make in-roads to university power. Caitlin Fischer and Dene Grigar direct their own programs at R-1 universities. But women of Judy Malloy’s generation were not encouraged to enroll in graduate programs.

In his 2012 book The Interface Effect, Alex Galloway glosses Lev Manovich’s Language of New Media: “to mediate is really to interface. Mediation in general is just repetition in particular, and thus the ‘new’ media are really just the artifacts and traces of the past coming to appear in an ever-expanding present” (10).

Literary history always reflects back an uncanny distortion of one’s own cultural moment, and here’s ours: at this conference I’ve heard a proliferation of tools, brilliant ways of doing new work. But I also hear, resonating in the back of my mind, Miriam Posner’s post from March 2012, “Some things to think about before you exhort everybody to code“:

The point is, women aren’t [learning to code]. And neither, for that matter, are people of color. And unless you believe (and you don’t, do you?) that some biological explanation prevents us from excelling at programming, then you must see that there is a structural problem.

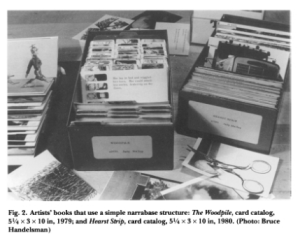

Judy Malloy is almost entirely a self-taught programmer. More specifically she’s a conceptual artist who dreamed up the idea of molecular storytelling while working with books she made from card catalogs in 1977. Later, as a single mom, she supported herself and her son working with technical information, including jobs as a technical librarian and a library assistant for several research and technical companies. On the WELL in 1986, she saw in the Art Com Electric Network bulletin board database a much more efficient mode of non-sequential storytelling than the card catalogs. She ended up writing 32 UNIX shells and even built in a Boolean operator (“and”). She built this system so that she could perform “live writing,” a “Homeric” experience she likens to Twitter today.

Extending Miriam’s point about women and code: even Judy’s undisputed capacity didn’t insulate her against sexism. Nor did the goodwill and respect from the other practitioners in her community. This is a human problem without a tool solution. But it’s possible that mindful use of tools could ameliorate the problem this reception history discloses.

The disequilibrium happened gradually over time. There is no villain twirling his moustache. While it circulated on the prestigious museum & gallery scene from 1987-1989, Uncle Roger excited interest in the popular press. It was singled out in the Centennial Edition of the Wall Street Journal (published on June 23rd, 1989), and mentioned in Newsweek. But the acclaim it garnered was pre-web. It is algorithmically invisible.

Afternoon’s ISBN, and Uncle Roger’s lack of one, is the second crucial differentiator in Judy and Michael’s divergent receptions. The presence or absence of an ISBN determined access: whether a work could be archived, collected and sold. The ISBN united disparate stewards (programmers/developers, librarians, academics, vendors) to collect and fortify those few works against bit-rot or obsolescence. The vast majority lacked an ISBN, and those were the responsibility of the authors to maintain or abandon. It would be much later (1997) before Malloy would author Uncle Roger in a browser-friendly format. By then excitement for the novelty of hypertext had given way to interest in Flash-based works. A moment had passed and with it, the power that comes from cultural currency.

“Structuralism is the midpoint on the long modern path toward understanding the world as system,” notes Alan Liu in his May 2013 PMLA article “The Meaning of the Digital Humanities.”

(…for example, system as modes of production, Weberian bureaucracy; Sausserian language; mass media & corporate society; neoliberalism; and so on). [These have] forced the progressive side of the humanities to split off from earlier humanities of the human spirit (Geist) to adopt a world view in which, as Katherine Hayles says, ‘large-scale, multi-causal events are caused by confluences that include a multitude of forces…. many of which are nonhuman.’ This is the backdrop against which we can see how the meaning problem in the digital humanities registers today’s general crisis of meaningfulness in the humanities (418-419).

The Malloy/Joyce reception history gives us a cogent example of how “the meaning problem” is a human and nonhuman collusion. “Michael Joyce” is a searched term linked forever by page-rank algorithms to “hypertext” and “electronic literature.” We here at DH 2013 learned about auto-completion algorithms in Anna Jobin and Frederic Kaplan’s talk in which they asked: “are Google’s linguistic prostheses biased toward commercially more interesting expressions?” Evidence they presented suggests that it is. Given that afternoon could be purchased and Uncle Roger could not, we can see how the financial interests of the New York Times and Amazon would begin to align, and how that alignment would manifest itself algorithmically.

It’s also worth noting that even if he had sought one, there is no reciprocal term that Coover could have used to deem Malloy a progenitor. “The grandmammy of hypertext fiction”? The “grand dame of hypertext fiction”? That would not work.

Put bluntly, the language to represent Judy Malloy’s achievement did not exist for Coover. He’s a wily guy, and he could have invented something. But it was not thinkable: to look to the west coast for literary origin, to esteem comedy more than tragedy, to recognize coterie distribution over a press, to praise a single mom with a Bachelor’s degree over a young male novelist with a print novel under his belt, and an MFA from the Iowa Writer’s Workshop. Such are the human judgments that launch a million clicks.

Coover didn’t invent “granddaddy” to describe Michael Joyce’s fiction. He invented Michael Joyce to inhabit “granddaddy.” In 1992, I wonder whether folks at Vassar, where Michael Joyce teaches, noted Coover’s pronouncement. Maybe someone cut it out from the Times and taped on the door of the English department or tacked it on a cork bulletin board. It would not have been conceivable in 1992 that the impact of that endorsement would be measurable, let alone field-defining, 20 years hence. But distant reading permits us to see just that.

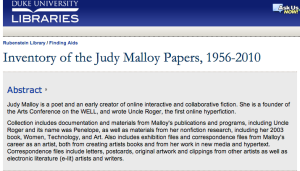

By way of conclusion I return to Alan Liu’s argument about the “crisis of meaning” in the humanities. I offer you a tableau. Duke University’s Rubenstein Library purchased Judy Malloy’s Papers. The collection features Judy’s

• Printed Materials

• Notebooks

• Early Artists Books

• Writings and Programming

• Exhibitions, Talks and Readings

• Correspondence

• Media by Other Artists and

• Personal Materials

It is 15.6 linear feet. 13,200 items.

Judy herself, however, has a 1-semester Anschutz Distinguished Fellowship in American Studies at Princeton this fall. She continues to seek a university job.

This is the signal gesture of the neoliberal university: to regard thinkers as content providers. To make financial commitments toward what can be digitized (and scaled) but less and less to people themselves. Code expertise is no safeguard. Publication is no safeguard. Collegial esteem and prolific output are no safeguard.

Last night Willard McCarty said, you do it for love. I see that, feel that, and yet am suspicious of that.

Post-Script

October 17, 2013

Judy Malloy notes this correction: “[T]oday being #ADL13 [Ada Lovelace Day] I have a request. In your otherwise wonderful article about Uncle Roger, you say that I am a self taught programmer. Actually that isn’t true. I did a graduate seminar in Systems Analysis at the University of Denver and I took a company sponsored course in FORTRAN when I worked at Ball Brothers Research Corporation in Boulder, where I headed a team that created a computerized library catalog in 1969, a time when this was an accomplishment. However, I did teach myself UNIX shell scripts and BASIC in order to create Uncle Roger. Generally it isn’t to difficult to move between similar systems.”

Pingback: He’s not the linkspam; he’s a very naughty boy (2 Aug 2013) | Geek Feminism Blog

Pingback: Labor of Love? | triproftri

Pingback: Ladies Last: Eight Inventions by Women That Dudes Got Credit For

Pingback: Ladies Last: Eight Inventions by Women That Dudes Got Credit For | The Daily Drudge Report

Pingback: Never Neutral: Critical Approaches to Digital Tools & Culture in the Humanities | Josh Honn

Pingback: Privacy, Obscurity, Openness, & Privileging Already Privileged Notions | Laurie N. Taylor

Pingback: Cumadóirí Dearmadtha ag an Stair | abairliom