On April 25th, my local school board voted to close just one elementary school, Palisades, in Sept. 2011.

This decision surprised the 250 people crowded in the high school library, where board members, seated behind a long table, faced them and publicly voted. It surprised us because in the 90 minutes leading up to the vote, board members laid out the rationale for closing 3 schools and moving 6th graders from elementary school to middle school. Further, the cuts and reconfiguration were strongly endorsed by both of the official parental-input groups, Site Council and the Committee on Reconfiguration.

The Board slowed the process: closure of the other two elementaries and 6th grade reconfiguration is slated to happen Sept. 2012.

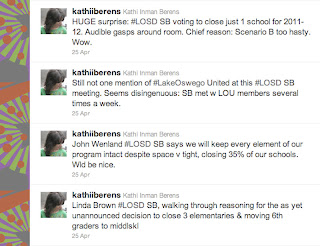

You can read my live Tweets here. To increase the size of my Tweets, hit the command key and the +. Or, in your browser’s dropdown menu, select View–>Zoom In. The first post is the one at the bottom; read up to experience them in order.

Next-day, traditional media coverage of the vote can be viewed in the Lake Oswego Review and Oregonian.

Twitter informed the community about the meeting’s result IRT [in real time]. It changed how we build consensus. District Superintendent Bill Korach customarily builds consensus by convening a lot of face-to-face meetings. He works hard to allow many people to participate in decision making process. I salute him for that! But social media can open the door wider, and it opens on demand.

The LO United site, created and maintained by a small band of local parents amassed facts. Its members, including me, left digital traces of conversations across platforms (most notably Facebook and the comments stream of our local newspaper, the LO Review).

Social media also made clear that our actions as a community were viewable by people who live beyond it.

To get a sense of just how pervasive even a droplet in social media can be, consider this anecdote from USC Annenberg librarian Avril Cunningham, who shared how a Tweet she sent to her 150 followers got retweeted and was seen within 24 hours by up to 5000 people on Twitter. Cunningham presented this case at last week’s USC 2011 Teaching With Technology Conference. Avril’s is one tiny example of how social media can spread information beyond where we might intend it to go. Our school closure debate, with its many passionate participants, probably sent its social media tendrils out to the tens of thousands. Some people in my Twitter community passed along to their followers URLs to the videos I shot.

Why does social media matter in this example of local politics?

It is still a new thing for us to conceive ourselves as being “always online”; but that’s exactly what smartphones enable. Being “always on” doesn’t mean being exclusively online, as we are when we’re focused on a specific task at our computers. It means we’re always aware that we could be online at any moment: snap a photo and post it to Flickr or FB; consult an app to find a restaurant or play a game; Tweet a URL; access a map to figure out where you are or where you want to go; drop a pin so it’s faster to find next time. Always on. The gadgets and platforms are so seamlessly integrated that we’re no longer aware of being “on,” as we were when we had to do everything at a desktop. Our collective mindset is catching up with the actual practice of being Always On. It’s changing how we make collective decisions.