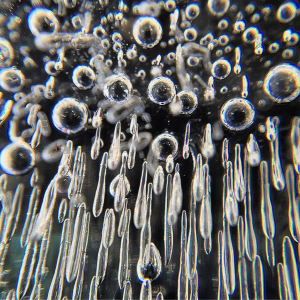

Image: Morgan Stone Grether. Used with permission. instagram.com/grether

Higher education is experiencing its Napster moment, its Amazon moment, and administrators are implementing online learning modules to compete. Disintermediation: what iTunes did to record stores and Amazon did to bookstores, textbook companies are beginning to do to residential university classrooms. University of Southern California Annenberg journalism professor Gabriel Kahn reported in Slate last September that universities’ rapid uptake of online classroom modules is a plug-and-play solution for entire courses that universities used to design and implement themselves. Kahn notes:

Companies such as Pearson, McGraw-Hill, and Wiley—the heavies of the college textbook market—have produced bundles that are basically a turnkey solution for basic chemistry or econ 101 and dozens of other classes, most at the introductory level. These courses feature content vetted by experts, slickly produced videos, and a load of interactive tests and quizzes. Some are so advanced that they can simulate a physics experiment, engage a student in a developmental psychology exercise, or even run software that grades an 800-word essay. They provide pretty much the entire course experience, without much interaction with a professor and without the hassle of showing up to class on time—or, for some instructors, the hassle of teaching.

Having taught for three years predominantly in an experimental classroom that’s both live and virtual, I know that on-demand interactive modules don’t yet approximate a seminar’s communal, improvisational dynamic. Synchronous classroom meeting software (I used Elluminate and then Adobe Connect) is still in its Ed Sullivan days. Software is good at facilitating standardized data collection of learning outcomes across the disciplines. Such affordances might look alluring as more instruction moves online.

Online learning modules are the opposite of what the digital humanities seek to foster. Julia Flanders notes that digital humanities should generate “productive unease,” the “irritation that prompts further thought and engagement. . . . [W]here that sense of friction is absent — where a digital object sits blandly and unobjectionably before us, putting up no resistance and posing no questions for us — humanities computing, in the meaningful sense, is also absent” (paragraph 12).

Interfaces are not neutral. They are sufficiently nuanced and political that the Terms of Service can be dozens of pages long. People usually notice interfaces only when they stop working– when an app shuts down, or loses connection to the Internet, or the phone drops a call. Interfaces are designed to be “frictionless,” to adapt Flanders’ term. Software updates make computational processes more invisible, more “intuitive,” as Apple calls it. Algorithmic anticipation might be nice for turning up a furnace. It might even be great for working through engineering problem sets. But it’s stupefying as a critical learning environment.

Digital humanists make many of their resources open, public and freely available. DHers’ moral commitment to public good is also an efficient way to diversify the field. Generosity is evolutionarily advantageous.

But how many teaching-only faculty can afford to take up DHers’ offer of free tools and training?

What if “time” and most faculty members’ inability to defend against its appropriation prevents teaching-only faculty–the majority of the professoriate–from integrating digital tools into their work?

Free tools might be a necessary but insufficient condition to provide access.

Digital humanities extends “our oldest inherited pedagogical belief as humanists. We don’t teach answers,” Paul Fyfe observes. “We teach students how to ask better questions.” The forthcoming Digital Pedagogy in the Humanities book, to be published by MLA in 2016 both open access and in print, curates the best 500-550 teaching resources focused on fifty keywords. (I curated the “Interface” entry.) Universities are charged to increase student digital literacy. But how to ensure the digital literacy of teaching-only faculty who have little to no support for professional development?

Here’s my provocation: Don’t just make tools freely available. Pay adjuncts and other teaching-only faculty for their *time* to learn them.

Academics accept overwork as a condition of our lives. We work weekends, defer sleep and rest, “catch up” on grading during spring break, make “vacations” out of conference travel. But it’s a mistake to universalize the culture of overwork. Overwork on the tenure line is an investment in professional promotion. Overwork among adjuncts is just the condition of keeping one’s job(s).

Feudal appropriation of adjuncts’ time is a DH issue. Last month Arizona State University decided to increase the teaching load of its first-year comp instructors by 25% without any increase in pay. Arizona State mandated that these instructors, many of whom are Ph.D. alumni of Arizona State, add a fifth class to their teaching load, putting their teaching load at 5/5, 125 students per term. Tenured and tenure-line faculty retain a 2/2.

It’s quite possible that as digital humanities shifts the disciplinary landscape not just of research but also of the teaching of writing, writing faculty may be expected to integrate digital tools even if they have no paid support for doing so.

Who will pay adjuncts to learn the digital tools that DHers make available?

Financial commitments from the Modern Language Association, the National Council of Teachers of English, the American Historical Association, the Allied Digital Humanities Organizations and other professional bodies should pay adjuncts and other teaching-only faculty to get digital training. Such organizations are mostly run by tenured faculty who have historically not seen alignment between adjuncts’ needs and their own.

But there’s a self-interested motive in fortifying adjuncts with digital tools. Harvard Business School professor and “disruption” expert Clay Christensen, who keynoted the prestigious EDUCAUSE conference September 2014, predicts that tenured faculty might find less demand for their services as adjunctification creeps inexorably up the food chain.

“Since 2005,” Gabriel Kahn reports, “universities have hired part-time faculty at nearly twice the rate as full-time faculty.” The Modern Language Association’s Report from the Task Force on Doctoral Study (2014) acknowledges that depressed hiring conditions since 2008, not candidates’ lack of preparation or aptitude, are responsible for the downturn in tenure-line hiring.

What would “paying” an adjunct to learn digital tools look like? Buy a contingent faculty member out of one class for one term and stipulate that the time be spent in DIY, on-demand digital tools training. Pay adjuncts to attend in-person training institutes like Digital Humanities Summer Institute or the Digital Pedagogy Lab. Follow up to see how such training changes classroom practice, whether or not it creates conditions of increased job security and even job satisfaction.

Maybe you’re thinking: there is no way anybody will fund this.

“What do we have left if we shouldn’t settle for just being ‘nice’ or ‘respectful’?” asks Elizabeth Losh of the digital humanities in her scholarly blog Virtualpolitik.

“Even in fields in which sole authorship is the norm, [scholarship] has always been collaborative” Kathleen Fitzpatrick declares (12). Similarly, teaching has always been collaborative. Most students graduating from English departments today are taught by a mix of faculty at all ranks.

Paying adjuncts to learn digital tools might look like generosity.

In hindsight, it may just look like survival.

***

I will deliver this talk as part of a roundtable discussion at the Modern Language Association Convention in Vancouver, BC, Saturday 11 January in the Vancouver Convention Center East, Room 16, at 8:30AM. The panel is called “Disrupting the Digital Humanities.” Join the conversation in real time or whenever: #MLA15, #s448, @kathiiberens.

Works Cited

Fitzpatrick, Kathleen. Planned Obsolescence: Publishing, Technology and the Future of the Academy. New York: NYU Press. 2011.

Flaherty, Colleen. “One Course Without Pay.” Inside Higher Education. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2014/12/16/arizona-state-tells-non-tenure-track-writing-instructors-teach-extra-course-each Accessed 2 January 2015.

Flanders, Julia. “The Productive Unease of 21st-century Digital Scholarship.” Digital Humanities Quarterly. 3.3 (2009). http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/3/3/000055/000055.html Accesssed 2 January 2015.

Frost-Davis, Rebecca, Matthew Gold, Katherine Harris and Jentery Sayers. Digital Pedagogy in the Humanities. New York: Modern Language Association, 2016. Print and online open access. https://github.com/curateteaching/digitalpedagogy/blob/master/announcement.md Accessed 2 January 2015.

Fyfe, Paul. “How to Not Read a Victorian Novel.” Journal of Victorian Culture 16.1 (Spring 2011): 102-106.

Kahn, Gabriel. “College In a Box: Textbook Giants Are Now Teaching Classes.” Slate. http://www.slate.com/articles/life/education/2014/09/online_college_classes_textbook_companies_offer_courses_with_minimal_university.html Accessed 2 January 2015.

Losh, Elizabeth. “Respect, Niceness and Generosity.” Virtualpolitik. http://virtualpolitik.blogspot.no/2014/08/respect-niceness-and-generosity.html Accessed 2 January 2015.

Modern Language Association. Report of the Task Force on Doctoral Study (2014). http://www.mla.org/report_doctoral_study_2014 Accessed 2 January 2015.

Smith, D. Frank. “EDUCAUSE 2014: Online Learning Could Fundamentally Change Role of Universities.” EdTech Magazine. http://www.edtechmagazine.com/higher/article/2014/09/educause-2014-online-learning-could-fundamentally-change-role-universities Accessed 2 January 2015.